This article was originally published as part of our Spring 2021 Newsletter. Click here for the full issue.

One year ago, in spring 2020, the novel coronavirus became truly recognizable as a global pandemic. The first deaths outside of China, including in Europe and the United States, were reported in February, and by the end of March, widespread lockdowns had brought daily life to a halt. The direct impact of the disease over the last twelve months has been both immense and tragic, with over 2.5 million recorded deaths worldwide. But, although it is widely discussed, the mental health impact of the pandemic is harder to measure.

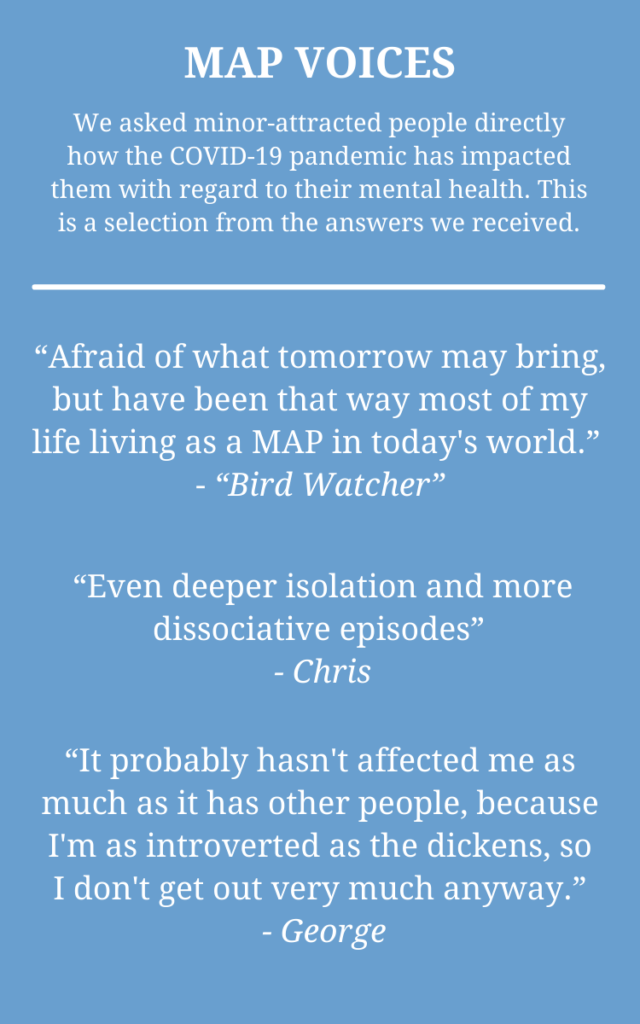

We do know that the pandemic has decreased measures of mental health around the world. The B4U-ACT Signatory and Referral Program has also seen a sizable increase in requests for mental health care during this time. No studies have yet attempted to document the effects of the pandemic specifically on minor-attracted people. So, for context on how MAPs specifically may be impacted, we reached out both to therapists in the program and to minor-attracted people in various communities, including B4U-ACT’s own peer support group. The responses show the myriad of ways in which a singularly isolating year has impacted a uniquely demonized group of people.

The therapists who responded to our question about what had changed during the past year gave mixed answers. While none reported having any MAP clients who indicated that they were seeking therapy as a direct result of the pandemic, there were other indicators of the effect it has had.

Brian Finnerty (LPC), one of the therapists to whom B4U-ACT refers MAPs, has started working with multiple new clients since the pandemic began. “Of the six MAPs on my caseload right now, four of them began their work with me during COVID,” Finnerty told B4U-ACT. “No one has explicitly stated that COVID had any link to their decision to seek therapy. But I suppose having extra time at home and being exposed to additional stressors could have been a motivating factor in seeking out therapy.”

To understand the impact the pandemic has had, it’s first important to understand that minor-attracted people reach out to B4U-ACT’s referral service for a variety of reasons. Some may be dealing with stigma and minority stress related to their sexuality, while others may have general mental health concerns (e.g., anxiety, stress, relationship problems, substance abuse) for which they feel uncomfortable seeing a therapist who may be hostile to their sexual identity, distress over their sexual attractions directly, or a combination of these and other issues.

Pandemic related stressors can intensify any of these concerns, but also can’t be considered the only factor, even as requests for support increase. For example, Sona Nast (MSSW, LCSW, LSOTP), another therapist to whom B4U-ACT refers MAPs, noted of one client that while “these stressors have been topics of discussion during treatment, most of the issues he is working on have been long-standing and unrelated to the pandemic.”

Without dedicated studies, it’s not yet possible to measure whether mental health has been significantly more affected for MAPs than for other groups, or whether MAPs have been affected in a substantially different way. But it has become increasingly evident throughout the pandemic that marginalized groups have faced a disproportionate amount of its harms.

Research points to social support networks as a protective factor against adverse mental health effects. In addition, a recent study in Journal of Homosexuality identified gender and sexual minorities (although attraction to minors was not explicitly mentioned) as disproportionately more affected during this time by symptoms of anxiety and depression, and having lower perceived social support. With this in mind, it’s reasonable to consider that MAPs might have been more susceptible to the stresses of a pandemic that has left all of us more fatigued and lonely.

Research on minor-attracted people elucidates how mental health is greatly impacted by the stigma surrounding their attractions. Social withdrawal and avoidance are more common among MAPs as a result. B4U-ACT’s Summer 2011 survey of MAPs found that over half of those who had seen a mental health professional mentioned dealing with society’s negative response to their attraction as part of their goals. The need for MAPs to keep their attractions secret, and fear of discovery, can be debilitating to networks of social support, and result in increased levels of loneliness and isolation.

“I think COVID has affected us all,” Brain Finnerty reflected, “but I suspect that communities which already tend to be more isolated have probably struggled a bit more.”

Michael Harris, director of B4U-ACT’s Signatory and Referral Program, brought up another subgroup that might be particularly affected. “We have certainly seen an increase in requests during the pandemic,” Harris reported, “and an alarming number of them have come from minors themselves… In recent months we have heard from MAPs as young as 12 who are seeking help.”

Research indicates that minor-attracted people usually begin to realize that their sexuality is different from their peers’ in late childhood or adolescence, and youths beginning to realize they are attracted to younger children are especially at risk when it comes to adverse mental health outcomes, including suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. Given findings that children and adolescents in general have been at higher risk of depression and anxiety symptoms during the pandemic, the need to reach these people with care has never been greater.

While the B4U-ACT Signatory and Referral Program represents a venue through which this need can be met, more efforts are needed. “Although our network of therapists is ever expanding,” Michael Harris explained, “we still do not have representation in all the areas of the country, or for that matter the world, where MAPs seek assistance, and so we are constantly seeking additional therapists.”

The backbone of the Signatory and Referral Program is a confidential list of therapists who are willing to provide compassionate, affirming therapy for MAPs that meets their needs. We do not publicly disclose any therapist’s presence on the list without their explicit permission. Instead, MAPs seeking therapy are sent names and contact information from professionals on the list who can practice (either face-to-face or telemedically) in their area. Therapists who join the list are also asked to reflect the goals and values in our Principles and Perspectives of Practice and our pamphlet Psychotherapy for the Minor-Attracted Person, which is crucial in assuring that the MAPs we refer receive compassionate therapy focused on their well-being.

While there are other therapist lists available to MAPs, our signatory based program, which affirms to MAPs that they will be treated in line with best practices, with compassion and responsively to their needs, is unique. Our 2011 survey found that over half of surveyed MAPs had wanted to see a mental health professional at some point in time, but did not do so, mostly due to fear of a negative reaction from the professional, or fear of being reported to law enforcement, family, employer, or community.

Signatories to the referral list are addressing these concerns by making their services available to MAPs who may not otherwise feel safe seeking support. As we all try to move through this difficult time, B4U-ACT is committed to expanding and improving our resources for MAPs to meet the growing need. This includes the effort to expand our list of participating therapists in the referral program, as well as broadening to include professionals in a larger number of geographical areas.

Minor-attracted people who are struggling and considering professional mental health support are encouraged to contact B4U-ACT via email at findtherapist@b4uact.org. Mental health professionals wishing to accept MAP clients are encouraged to contact the Signatory and Referral Program through Michael Harris at signatorylist@b4uact.org.